I’m a certified Gilbert & Sullivan junkie, as are my husband and his family. When I was in grade school I had a set of Golden Something-or-Other records and a little record player (yes, it’s true), and one of those ancient disks had G&S selections on it. I can remember listening over and over again to the Mikado’s “My Object All Sublime” and trying to figure out what on earth the words meant about the punishment doled out to a “billiard shark” (whatever that was): “On a cloth untrue/With a twisted cue/And elliptical billiard balls!” I finally realized that this was a pool table with a distorted tabletop, cues and balls. I’ve seen numerous productions of The Mikado and even two performances of the Hot Mikado, a jazz version that is, like, totally great. (The gentlemen of Japan are dressed in zoot suits.) I’ve seen H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance on both film and in live performances. (Check out the Linda Ronstadt/Kevin Kline/Angela Lansbury version.) I’ve seen a live performance of Patience, one of the lesser-known in the canon. But until I participated in a concert that included the finale from The Gondoliers I’d never even heard of this particular creation.

Here are the words to this section of the operetta, sung by the whole company with great verve and a great deal of choreography as the curtain comes down::

Once more gondolieri,

Both skilful and wary,

Free from this quandary

Contented are we. Ah!

From Royalty flying,

Our gondolas plying,

And merrily crying

Our “premé,” “stali!” Ah!

So good-bye, cachucha, fandango, bolero —

We’ll dance a farewell to that measure —

Old Xeres, adieu — Manzanilla — Montero —

We leave you with feelings of pleasure!

First a couple of vocabulary issues: “cachucha, fandango, bolero” are all types of dances, and “Old Xeres. . . –Manzanilla—Montero” are all types of wine. (“Xérès” or “Jerez” is how the actual name for the Spanish wine that we call “sherry” is spelled. You may recall, by the way, that Carmen sings in her famous Act One aria that she is going to “dance the Seguedille and drink Manzanilla.” Linked video is of a concert version with Jessye Norman and Seiji Ozawa.) So at least some of the characters are saying good-bye and farewell to dancing and wine, leaving with “feelings of pleasure.” They have been freed from a “quandary.” And they’ll soon be merrily crying “premé” and “stali!” as they ply their gondolas. What gives?

In order to understand the finale completely we have to understand the plot, which is not that easy. Gilbert never let logic interfere with neat resolutions of the story. (Just like Shakespeare. Oh dear, did I just say that?) The plot turns on that hoary old chestnut, the babies switched at birth. Only in this case (follow me closely here), 1) The baby prince of Barataria, for reasons too complicated to explain here, has been kidnapped 20 years earlier and brought to Venice to be raised by a gondolier who had a son of his own, but 2) The gondolier father got the babies mixed up and then died before straightening their identities out, and 3) The heroine, Casilda, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Plaza-Toro, was married to the baby prince when she was only six months old herself, but 4) Now no one knows which of the two young gondoliers is the prince and therefore her husband, and 5) Of course, she’s in love with someone else, her parents having neglected to tell her that she was already married. In the end, we have yet another chestnut, the old nanny coming in to tell everyone which baby was which, although how she’s supposed to tell the two young men apart when she last saw them as babies . . . well, see comment about logic and plots above. But the nanny comes through. In order to prevent the real prince from being kidnapped, she says, such was her loyalty to the royal family that she substituted her own son for the prince. Therefore, the real prince, the one who should now be crowned king since the old king of Barataria has died, is the young man whom she has raised as her son. And that son is also the man that our heroine is already in love with. He’s been acting as her father the Duke’s servant.

Now we can take a look at the finale and make some sense out of it. The two gondoliers have been acting as joint kings of Barataria until their identities can be sorted out, but now they know that neither one is the rightful heir they’ll both be returning to their humble but honest lives as gondoliers. First, though, they’re having a big celebration in honor of the whole situation’s being resolved. They’re happy to find out that neither one of them is a bigamist (since both of them had gotten married before the whole baby nuptials thing was revealed). They praise the pleasures they’ve had during their kingship: wine and dancing. They’ve enjoyed it, obviously, but then they start saying their farewells. They are contented to be “once more gondolieri,” they are freed from the quandary of figuring out who’s the rightful king, and now they can go back to crying “preme” and “stali.” (Those two words are standard gondoliers’ calls meaning either “to your left/to your right” or “push in your pole/stop.” Has no one interviewed a living gondolier to ask which interpretation is correct? Apparently not.) So they leave the new royal couple with feelings of pleasure. All is resolved. (There is the little question of which one of the two is the old nanny’s real son and which the old gondolier’s son, but that issue is never addressed. I guess the question of royalty is the only important one.)

If you’d like to read an even longer explanation of the plot, with even more side snide comments and also indications of where the music fits into the libretto, go to “Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Gondoliers”: an annotated plot summary.”

If you’d like to listen to a superlative performance, see below.

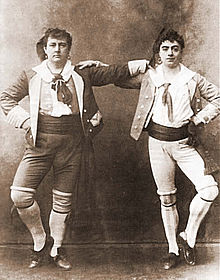

And, as a little final treat, here’s a photo of the two original gondoliers:

© Debi Simons

Hi there

I just wanted to let you know that I very much enjoyed your article on Ocho Kandelikas and wanted to let you know that Flory Jagoda is indeed still alive, living in Alexandria, VA.